Thursday, Apr 09, 2020 at 14:48

DOH!!

Thought I'd edited that off lol.

Correctamundo Barry. Thought we might as

well make it as interactive as possible given we're probably largely stuck at

home.

The

graves are located at

Mount Winter in the

Cleland Hills.

I've added a bit from my journals from our 2014 expedition with

well known

Alice Springs historian Dick Kimber. One of the conditions of our permit was that we undertook some

clearing and maintenance of the

grave sites for the Haasts

Bluff elders.

Mount Winter first appears on W H Tietken's plan of exploration in 1890 in his "Cleland Hills" and is believed to originate from Ernest Giles 1873-4 journey and be named after William Winter of Stanhope, Victoria, and later of Rocklands Station near

Camooweal, Queensland. Winter subscribed (financed) Giles exploration. The Luritja name for the area has always been ‘Puritjarra’ which simply means “shadow on

the rock”.

Nearby, in the shadow of this remarkable place lie the

graves of a father and son here who died in 1929. At that time a harsh drought was forcing

the desert people out of the country and into Hermansberg. Reaching Puritjarra, the old man was simply too weak to continue on and his son refused to leave him. They died together and were interred near each other with the massive bulk of Puritjarra to watch over them.

The number of millstones or grindstones about the place is simply incredible and you have to be very careful not to drive over them. Cautiously moving our way through this delicate area, we retreated to the dunes to the east of the Mount and set up

camp behind a belt of mulga. We can hardly wait to explore this fascinating area. We climbed to the top of a nearby dune at dusk to photograph the sunset.

and the next day;

Our first mission of the day was to clean up the areas surrounding the two

grave sites which we cleared of scrub and then swept clean with native brush. Returning to the vehicles, we packed our cameras and headed into the canyon. On the northern side, a high, ridge runs along until it meets the rocky walls of the Range. On the sandy valley floor, a creek bed winds it’s way out of

the gorge, the flow of water exposing the rocky nature of the underlying soil.

Of immediate impact were the sheer number of grindstones lying about the area. It was simply amazing. In one area I stood and within 10 square metres, counted more than a dozen grind stones intact with the remnants of many more broken implements lying about. It seemed that every

rock you turned had a grinding groove in it, on one side or both. Dick informed us that many of the Grindstones found in collections or front doorsteps around

Alice Springs had been “souvenired" from this area by the less scrupulous travellers from the 1930’s onwards.

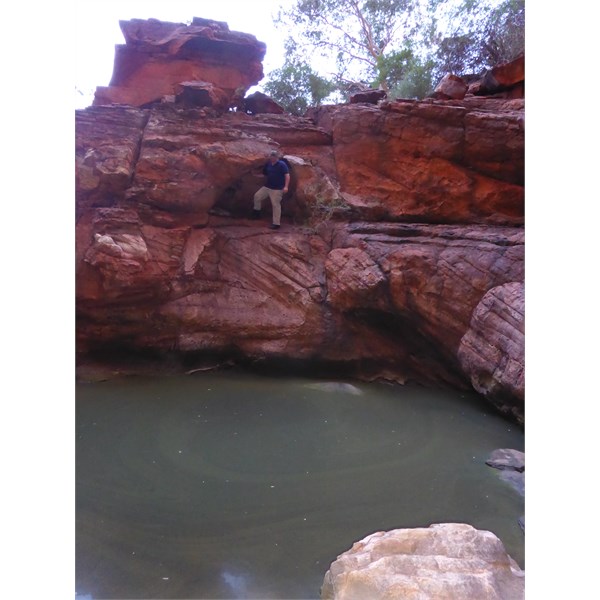

As we approached the end of

the gorge, the sand gave way to a slope of huge, rough boulders. We had to scramble over this jumble of room sized rocks and push our way through scrubby thickets finally reaching a fine

pool of water. Deep in shadow, the dark, cool climate promoted some very different types of vegetation including vines, mosses and lichens. The sheer

rock walls towered a hundred metres above us and it would have been most impressive to witness water flowing over this long drop into

the pool below.

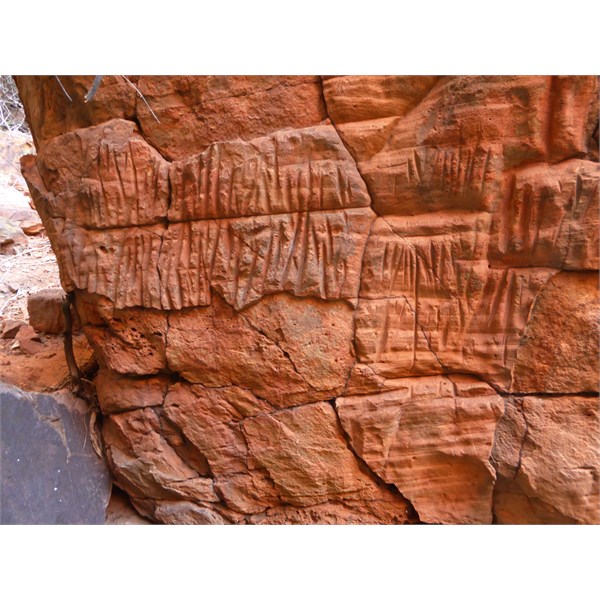

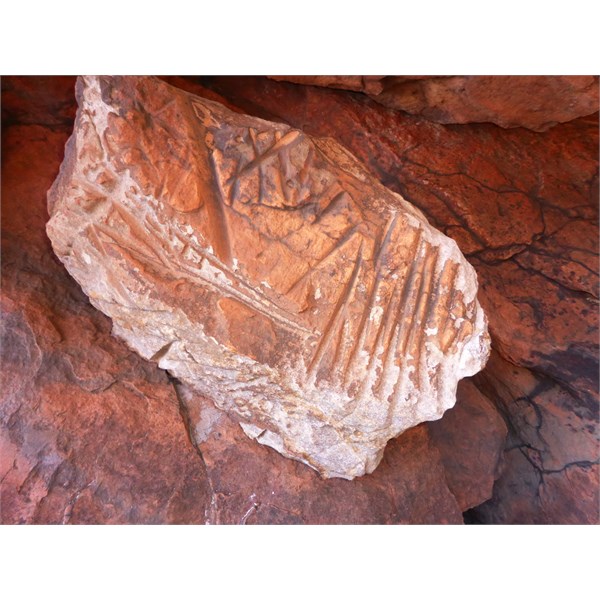

On flat surfaces and in caverns surrounding

the pool we found rocks thick with carved ‘rain lines’, grooves worn into the rocks as part of a rain making ceremony. Together with Scott I climbed up the walls above

the pool to investigate larger caverns where we found softer substrate weathered in remarkable honey comb patterns. From the edge of

the gorge, we gained a remarkable view back along the valley and onto the plains to the east. Carefully picking our way down from the

vantage point, we joined the group and retraced our steps back along the valley to

camp. A spot of lunch and we were on our way north west into the

Cleland Hills.

The

Cleland Hills are a low, western outlier of the

George Gill Range and are surrounded by sand plains and dune fields in the predominantly flat landscape of the

Great Sandy Desert. The Hills are mostly composed of Mereenie

sandstone and hold water that supports plant species with restricted ranges. The hills support open-woodland with an undergrowth of spinifex grassland.

Driving along the northern edge of this range, the geological history of the area is written deeply in the weathered

sandstone strata. In this area, the

sandstone takes a finely banded form in conical structures not dissimilar to that found in Purnululu (The Bungles) of WA. Weathering of the northern ridges has resulted in large caverns, many of which were used as a place of regular habitation by the nomadic desert people. One of the largest is also referred to as ‘Puritjarra’ and set the archeological and anthropological record of the red centre on its head with discoveries showing regular habitation of the

cavern for a period of 35,000 years. It is also a place that Dick played a significant part in the rediscovery of in the 1980’s.

Puritjarra was first discovered by Europeans in a 1969 expedition to the

Cleland Hills by Robert Edwards, curator of anthropology at the South Australian Museum. Edwards had found the place on foot after the radiator had boiled on his Land Rover, in remote country near the

Cleland Hills. He was still some distance from his destination at Thomas Reservoir (Alalya), where he was taking a party to photograph and document deep ancient

rock engravings. While waiting for the radiator to cool, Tjukadai, Edwards’ guide from Haasts

Bluff, took a walk towards Mt Winter. He returned with news of a

rock shelter with

cave paintings:

“We found it was huge — two hundred feet long and sixty feet high … Numerous ochre paintings were around the wall in red, white, yellow and black. There were simple hand stencils, hand prints, bird tracks, kangaroo tracks, circles and snakelike designs. Then, delightedly, we came upon ancient engravings ... But more precious, the floor of the main

cave was covered with pieces of charcoal, and a small

test pit showed many feet of accumulated occupation deposit”.

Excited by the discovery, but short of water and time, Edwards and his party had been forced to move on to reach Murantji

rock hole. Edwards never returned.

When the archaeologist Mike Smith began his work in Central Australia in the 1980s, he and his colleagues had evidence for people dwelling in the Central Australian deserts up to 3000 years ago. Puritjarra radically changed this. Smith grabbed at a chance opportunity and a permit to travel to Thomas Reservoir in September 1986. On the ground, with aerial photographs in hand, he begged a few hours to scout the Mt Winter area on foot. His mate, Dick Kimber, went south.

Within half an hour Smith struck the Puritjarra

rock shelter, one of the biggest he had seen. It was a veritable gallery of

rock art and it had an undisturbed earthen floor. The artifacts Smith dug from the site showed dates of 35,000 years, that is penetrating

well back into the Ice Age. This is a very long history of dwelling in a place where it is believed the current arid environment has existed for the past 100,000 years, conditions that made it difficult for people to find water, food and

shelter. Much of

the desert country was believed to have been empty of human habitation for between 10-15 thousand years until the retreat of the last ice age.

With Dick’s intimate knowledge of

the desert people, the Puritjarra area, Smiths work and the cultural significance and meaning of much of

the rock art, we were indeed fortunate and made our visit incredibly special. Dick was able to provide the stories of the etchings, stencils and art work. We listened with wrapped attention as he spoke of the emu dreaming which certainly put a lot of

the rock carvings into perspective for us. Puritjarra is one of the few

places where the hand stencils of children can be found adorning the gallery, much of the art being between 200 and 4700 years old.

Mt Winter - a brisk morning

Rain marker grooves

Pool at the end of the gorge

Pool

Grooves

Dick at the graves

Grinder

Dick at Puritjarra

FollowupID:

906788